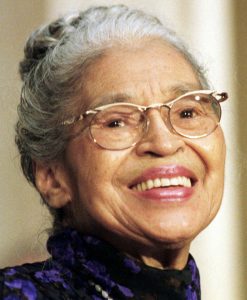

Black History Month: Rosa Parks: Sitting for Equality

Sitting for Equality – Rosa Parks

In the United States of America, the month of February is Black History Month. It is a time to remember the achievements that men and women of color made throughout the history of this country. From a time of slavery to a time of freedom that did not really feel all that free, to a movement that would change the nation forever, men and women of color have played key roles in making a better quality of life for all mankind.

Rosa Louise McCauley was born on February 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, Alabama. Her grandparents, both former slaves, took in Rosa and her mother after her mother divorced her father. From a young age, her grandparents instilled in her a belief of racial equality, however, Rosa grew up surrounded by racial discrimination. A standout moment in her childhood was her grandfather standing in front of their home with a shotgun, while members of the Ku Klux Klan marched down the street.

Rosa Louise McCauley was born on February 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, Alabama. Her grandparents, both former slaves, took in Rosa and her mother after her mother divorced her father. From a young age, her grandparents instilled in her a belief of racial equality, however, Rosa grew up surrounded by racial discrimination. A standout moment in her childhood was her grandfather standing in front of their home with a shotgun, while members of the Ku Klux Klan marched down the street.

Rosa was educated in a segregated one-room schoolhouse, to which she was forced to walk, while the white children were taken by buses to a newer school building. It was through buses that Rosa began to realize “there was a black world and a white world.” Rosa began attending a laboratory school set up by the Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes for secondary education but never completed her studies. She left to care for her ailing grandparents and mother.

Rosa McCauley became the more well-known Rosa Parks in 1932 when she married Raymond Parks, a barber and a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Even within the NAACP, Rosa continued to face discrimination, not for the color of her skin, but for her sex. Rosa was the only woman in the Montgomery chapter and the sectary for E.D. Nixon, who claimed “Women don’t need to nowhere but in the kitchen.” When Rosa questioned him about her position, he said, “I need a secretary and you are a good one.” Through her work with the NAACP, Rosa was exposed to, and researched, the legal problems of black men and women, such as the Scottsboro Boys, the rape of Recy Taylor, and the murder of Emmett Till.

By December 1, 1955, Montgomery, Alabama had passed a city ordinance segregating bus passengers by race. Specific rows of seats were reserved for whites only, designated by a sign on the bus, which drivers could move or remove altogether. Over time, drivers adopted the practice of moving the sign if the whites-only section filled up. Blacks were to move and give up their seats to the whites, even if it meant they had to stand.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa went to work, as usual. Her day was relatively normal, until her bus ride home. Rosa boarded the bus, paid her fare, and sat in the first row of the designated “colored” section of the bus. After several stops, the whites section had been filled, so the bus driver, James F. Blake, with whom Rosa had previously had a verbal altercation, moved the sign indicating where colored people could sit, back several rows. The moving of the sign meant that four black individuals, including Rosa, were now in the designated white section. The driver ordered them to move. Three of the passengers gave up their seats. Rosa moved too. Only she moved from her aisle to seat, to a window seat!

The murder of Emmett Till had a profound impact on Rosa and it was him that she thought of that day when she refused to move back into the newly designated “colored” section. The driver questioned Rosa as to why she did not move. Rosa responded, “I don’t think I should have to stand up.” When Blake threatened to call the police, Rosa stated, “You may do that.” Rosa said, many years later, that she had decided that, “I would have to know for once and for all what rights I had as a human being and citizen.” In her autobiography, she also clarified what she felt that day. Many have assumed she was simply tired that day and did not want to stand. Rosa says, “I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day…No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

The murder of Emmett Till had a profound impact on Rosa and it was him that she thought of that day when she refused to move back into the newly designated “colored” section. The driver questioned Rosa as to why she did not move. Rosa responded, “I don’t think I should have to stand up.” When Blake threatened to call the police, Rosa stated, “You may do that.” Rosa said, many years later, that she had decided that, “I would have to know for once and for all what rights I had as a human being and citizen.” In her autobiography, she also clarified what she felt that day. Many have assumed she was simply tired that day and did not want to stand. Rosa says, “I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day…No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

Rosa Parks was arrested and charged with violating segregation laws. She was bailed out by Edgar Nixon, president of the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP, and a white friend, Clifford Durr. Rosa’s arrest spurred the Women’s Political Council into action. Alabama State College professor Jo Ann Robinson stayed up all night to created 35,000 handbills announcing the bus boycott.

On December 5, 1955, the bus boycott began. It rained, but the black community persevered. A new organization, the Montgomery Improvement Association, led by Martin Luther King, Jr., at the time a relative unknown, was established to lead the boycott effort, which lasted for 381 days. During that time city buses stood idle and the city severely suffered financially from the boycott.

The NAACP decided that Rosa was the ideal plaintiff for a test case against the city and state segregation laws. Several women before Rosa had also refused to give up their seats on public buses, however, Rosa was chosen because she was a responsible, mature woman who maintained a good reputation. She was also securely married and employed, had political awareness, and carried herself in a quiet and dignified manner.

While Rosa’s lawsuit made its way through the state courts, another lawsuit Browder v. Gayle made its way through the federal courts to, eventually, the Supreme Court of the United States. In its decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the segregation of public buses was unconstitutional. Rosa did not participate in the Browder lawsuit, as there was fear that she would be accused of attempting to circumvent the Alabama state court system.

Although an icon for the Civil Rights movement, Rosa’s life was anything but peaceful. She was fired from her department store job, her husband quit his job after his boss prohibited him from mentioning his wife, and the couple constantly received death threats. In 1957, Rosa and her husband moved to Hampton, Virginia, before moving with her mother to Detroit, to be with her brother and sister-in-law. In Detroit, Rosa noted that housing, school, and service segregation continued to exist.

Rosa remained politically active, supporting the Selma-to-Montgomery Marches, various freedom organizations, desegregation at all levels, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. She also became the secretary for State Representative John Conyers, a position she remained in until she retired in 1988. Rosa also continued with her activism work, donating nearly all the money she made from speaking and appearances.

Rosa remained politically active, supporting the Selma-to-Montgomery Marches, various freedom organizations, desegregation at all levels, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. She also became the secretary for State Representative John Conyers, a position she remained in until she retired in 1988. Rosa also continued with her activism work, donating nearly all the money she made from speaking and appearances.

In the decade of 1970, Rosa lost her husband, brother, and mother to various illnesses. It was a difficult time for her, although she continued to work on various projects and served on the Board of Advocates of Planned Parenthood. Rosa began to slow as she aged and limited her activities.

Rosa Parks died of natural causes on October 24, 2005, in her Detroit apartment. She was 92 years of age. After her death, she was afforded the honor of lying in state at the Capitol rotunda. She was the first non-government official, the first woman, and the second black individual. The then-current Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice spoke at Rosa’s memorial, noting that if it hadn’t been for Rosa’s stand – sit – she would likely have never been able to achieve the position she held. Rosa was buried alongside her husband and mother.

For more information regarding how your financial support can help, please click here.