TFFCM Celebrates Black History Month: The Tuskegee Airmen Breaking Barriers

Tuskegee Airmen Breaking Barriers

In the United States of America, the month of February is Black History Month. It is a time to remember the achievements of men and women of color made throughout the history of this country. From a time of slavery to a time of freedom that did not really feel all that free, to a movement that would change the nation forever, men and women of color have played key roles in making a better quality of life for all mankind.

The Wright brothers took their first flight in 1903. Six short years later, in 1909, the United States military began using airplanes. World War I was the first major conflict to significantly utilize aircraft. However, in the United States, the honor and privilege of flying a plane was reserved only for white males. It was not the only limitation placed on African-Americans in the military. Many top officials believed that African-Americans were too uneducated, untrainable, and unreliable for many positions within the military.

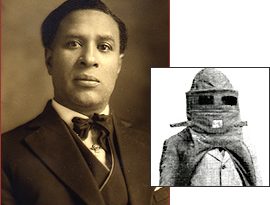

But African-Americans were not to be deterred. In 1917, several African-American males attempted to become aerial observers, however, their request was rejected. For the next two decades, African-Americans advocated for the right to enlist and train as military aviators, with little success. In 1939, Congress finally passed a bill that designated funding for the training of African-American pilots, albeit in civilian flight schools. Per tradition, however, black men were trained separately from their white counterparts. One of these schools was at the Tuskegee University, a private, black university started by Booker T. Washington in the late 1800s, and located in Tuskegee, Alabama.

But African-Americans were not to be deterred. In 1917, several African-American males attempted to become aerial observers, however, their request was rejected. For the next two decades, African-Americans advocated for the right to enlist and train as military aviators, with little success. In 1939, Congress finally passed a bill that designated funding for the training of African-American pilots, albeit in civilian flight schools. Per tradition, however, black men were trained separately from their white counterparts. One of these schools was at the Tuskegee University, a private, black university started by Booker T. Washington in the late 1800s, and located in Tuskegee, Alabama.

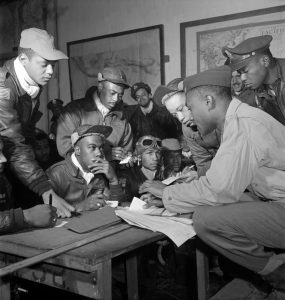

When the United States entered World War II, they were in need of pilots. The first all-black flying unit was created – the 99th Pursuit Squadron, with 47 officers and 429 enlisted personnel. The military continued to insist upon strict selective policies to ensure that only the best and brightest of African-Americans were permitted to fly. Even with these restrictions, the Army Air Corps (later the United States Air Force) received an abundance of qualified applicants, including many who had participated in the Civilian Pilot Training Program at Tuskegee.

Over the next several years, the Tuskegee Army Air Field would continue to grow and expand. It eventually becoming the only location to perform all three phases of pilot training. Unfortunately, despite the success of the program, those who completed the training were often not assigned potions. Some officers felt that it was inappropriate to have African-American officers serving over white enlisted men.

The 99th was considered combat-ready in April of 1943 and was sent to North Africa to join the 33rd Fighter Group. The first combat mission for the 99th occurred on June 2, 1943. They were to join an attack on a strategic island in the Mediterranean Sea. The mission was a rousing success, taking the island!

By the end of February 1944, more graduates from Tuskegee were ready for combat missions, and the all-black 332nd Fighter Group was sent overseas with three fighter squadrons: the 100th, 301st, and 302nd. All members of the group, from the pilots to the mechanics, to the administrative clerks, to the control tower operators, were African-American personnel. The 332nd would be joined by the 99th at Ramitelli Airfield in Italy, giving it four fighter squadrons. The 332nd was to provide flying escorts for heavy bombers. The unit’s aircraft were identified by a crimson marking to the tail of the aircraft, earning the airmen the nicknames of “Red Tails” or “Red-Tail Angels.”

By the end of February 1944, more graduates from Tuskegee were ready for combat missions, and the all-black 332nd Fighter Group was sent overseas with three fighter squadrons: the 100th, 301st, and 302nd. All members of the group, from the pilots to the mechanics, to the administrative clerks, to the control tower operators, were African-American personnel. The 332nd would be joined by the 99th at Ramitelli Airfield in Italy, giving it four fighter squadrons. The 332nd was to provide flying escorts for heavy bombers. The unit’s aircraft were identified by a crimson marking to the tail of the aircraft, earning the airmen the nicknames of “Red Tails” or “Red-Tail Angels.”

Throughout the war, the Tuskegee Airmen earned three Distinguished Unit Citations. One of these Citations was earned for the longest bomber escort mission. The group escorted bombers over 1,600 miles into Germany and back, to destroy a massive enemy tank factory, which was heavily defended by the German air force. Individually, pilots in the 332nd accumulated a total of 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses for missions all over Italy and occupied parts of central and southern Europe. Pilots in the 99th also set a record from destroying five enemy aircraft within four minutes.

There were a total of 992 pilots trained at Tuskegee between 1941 and 1946. Of the 992 graduates, more than 350 were sent overseas, where 84 lost their lives, including 32 who were captured as prisoners of war. The Tuskegee Airmen were credited with flying 1,578 combat missions and 179 bomber escort missions. They only lost a total of 27 bombers that they were escorting, on seven different missions. Other (white) bomber escort groups lost an average of 46 bombers during the same period. The Tuskegee Airman destroyed 112 enemy aircraft in the air and another 150 on the ground. Additionally, they put a destroyer class ship out of action and destroyed a total of 40 other boats and barges. Pilots in the 332nd also earned various other accommodations, including at least one Silver Star, 14 Bronze Stars, 744 Air Medals, and 8 Purple Hearts.

There was no doubt that the Tuskegee Airmen were some of the best pilots during the war, with bombers often requesting the 332nd as their escort, however, these brave men continued to face racism at home and from other units, both during and after the war. But they continued to demonstrate their enviable skills as pilots. In 1949, four of the pilots from the 332nd Fighter Wing participated in the annual US Continental Gunnery Meet in Las Vegas, Nevada, which required shooting aerial targets, ground targets, and dropping bombs on ground targets. The group took first place with a perfect score; they did not miss a single target!

There was no doubt that the Tuskegee Airmen were some of the best pilots during the war, with bombers often requesting the 332nd as their escort, however, these brave men continued to face racism at home and from other units, both during and after the war. But they continued to demonstrate their enviable skills as pilots. In 1949, four of the pilots from the 332nd Fighter Wing participated in the annual US Continental Gunnery Meet in Las Vegas, Nevada, which required shooting aerial targets, ground targets, and dropping bombs on ground targets. The group took first place with a perfect score; they did not miss a single target!

When military segregation was ended in 1948, by President Harry Truman, the veteran Tuskegee Airmen found themselves in high demand, both in the military and civilian world. Additionally, the Air Force required that those still serving be reassigned to formerly all-white units, based on their qualifications.

The Tuskegee Airmen set out to prove that they could fly just as well as their white counterparts – the Tuskegee Airmen ended up proving they could fly better! After the war, some Tuskegee Airmen continued to work in aviation and the military.

For more information regarding how your financial support can help, please click here.